The Source of True Positivity

What is the value of life? In a world of hunger, misery, continual acts of terrorism and war? In the face of the destruction, hatred, fear and greed that seem to dominate the world today, how can we maintain a positive attitude? It seems impossible. The question also arises for every single human being: don’t illness, constant pain and strokes of fate seem to rob life of all value? Put on one side of the scales all the positives we have ever experienced and all the negative on the other. It is clear that the negative experiences weigh heavier for the great majority of people. A completely negative balance. Isn’t suicide or “exit” the most sensible solution to put an end to the negative spiral of value?

So are we becoming pessimists? That was the philosophical consequence of Schopenhauer and Eduard von Hartmann and of all those who, like them, merely add and subtract. The calculation is accurate, but the human I reckons differently. It sees a different relationship between positive and negative experiences than adding and subtracting them. It carries out a division with them. Express all positive and negative experiences as a fraction: above the line (numerator) all the positive, and below the line (denominator) all the negative experiences. This fraction can never be zero! For this purpose, either the numerator would have to be zero or the denominator would be approximately infinite. Who can say that he did not experience anything of value until his last breath? Who can say that the number of his sufferings is infinite? The divisive relationship of positive and negative experiences therefore always retains a positive value, however slight it may be or appear to be. To experience this sober realization, gives our life an experiential, positive basic value. The I divides. This was the solution to the problem of value, as Rudolf Steiner stated in the thirteenth chapter of his Philosophy of Freedom. The ego divides; but it can only divide because it is itself indivisible, because it is in-dividuality.

The positivity, which Steiner also calls the “sense of affirmation,” is the o

nly one of Steiner’s six basic exercises known as the subsidiary exercises which he illustrates by means of a legend from the life of Christ: “There is a beautiful legend of Christ in Persian poetry, which brings to mind what is meant by this quality [of positivity]: a dead dog is lying on a path. Christ is also among those passing by. Everyone else turns away from

the ugly sight of the beast; only Christ speaks admiringly of its beautiful teeth. That is how o

ne can feel about things; in everything, even the most

adverse, those who are serious seekers may fin

d something worthy of appreciation. And what is fruitful in things is not what they lack, but what they have.”1 For the divisory way in which the I beholds them, what they have is most definitely the positive th

ing about them.

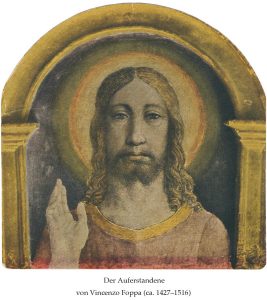

Christ is the World-I, the great model for our microcosmic I, our individuality. He remained throughout absolutely unspeakable suffering in a state of total positivity. He is the true, essential source of all true positivity in our soul-spiritual striving.

T.H. Meyer

_________________________

1 Rudolf Steiner, Die Stufen der höheren Erkenntnis, GA 12.